The rest of the world

In 2023 Climate Explorer had temperature records for Australia, New Zealand and the UK. We wanted to add temperature records from all around the world. Finding a dataset that fitted our requirements wasn’t easy. Below are the required criteria.

- A dataset that has unadjusted (what was recorded on the gauge) and adjusted records (corrections due to changes at the site and fixes for errors).

- Only the best quality and longest running stations, from the tens of thousands of available sites around the world.

- A fine-grain resolution to support the different graphs in ClimateExplorer. ClimateExplorer was built with daily minimum and maximum records in mind. ClimateExplorer doesn’t work with a higher resolution than daily records. Only since the advent of digital recording (around the 1970s and 1980s) has hourly or more frequently recorded temperatures been available and we wanted data that was longer-term. ClimateExplorer can also work with monthly and yearly records.

- Data from really existing stations

- Precipitation data for the selected stations

Initial investigation

The advantage of starting with ACORN-SAT was that these criteria were easy to meet because; 1) ACORN-SAT is an adjusted data-set and the Bureau of Meteorology make the unadjusted data publicly available via their website. 2) ACORN-SAT is a 112 station subset of Australia’s stations, already selected for quality and longevity. 3) ACORN-SAT is a daily dataset of maximum and minimum temperatures. 4) It’s from known stations. 5) We were able to find the precipitation data from the BoM and link it to the ACORN-SAT temperatures.

NCEI/NOAA have a few products that looked suitable. They are:

- Global Hourly - Integrated Surface Database (ISD) - this seemed ideal at first because it has hourly data as well as a daily summary of temperature with many other data types. We could pre-process hourly records into daily records and then build in functionality to support other types of data (e.g., windspeed).

- Global Historical Climatology Network daily (GHCNd)

- Global Historical Climatology Network monthly (GHCNm)

We assessed each product with the criteria specified above, at the start of this article.

Criterion 1 - adjusted and raw datasets

We started by looking at ISD. The ISD doesn’t have an adjusted dataset. Maybe that was okay if the other criteria were met. The nice thing about ISD is that it records, as meta-data, when the station started operating and when it shutdown (if it has). The downside, however, is that it wasn’t until we started downloading all of the climate data (many gigabytes) that we saw how much of it was missing for some stations. It’s a challenge to describe a station as “good” when, although it’s been running for one hundred years, it’s missing decades of data during that time. Frustrated, we put on hold integrating ISD into ClimateExplorer and further explored what datasets were available.

GHCNd was looked at next. GHCNd is also solely an unadjusted dataset. From the Methods:

Unlike GHCNm, GHCNd does not contain adjustments for biases resulting from historical changes in instrumentation and observing practices. It should be noted that historically (and in general), the deployed stations providing daily summaries for the dataset were not designed to meet all of the desired standards for climate monitoring. Rather, the deployment of the stations was to meet the demands of agriculture, hydrology, weather forecasting, aviation, etc. Because GHCNd has not been homogenized to account for artifacts associated with the various eras in reporting practice at any particular station (i.e., for changes in systematic bias), users should consider whether or not the potential for changes in systematic bias might be important to their application. In addition, GHCNd and GHCNm are not internally consistent (i.e., GHCNm is not necessarily derived from the data in GHCNd) until the release of GHCNm version 4.

Out of the three NOAA products, GHCNm is the only one that meets criterion 1. NOAA explain the issue and the adjustment process as well as publishing the unadjusted data along with the adjusted data.

Nearly all weather stations undergo changes to data measurement processes and infrastructure at some point in their history. Thermometers, for example, require periodic replacement or recalibration, and measurement technology has evolved over time. Temperature recording protocols have also changed at many locations from recording temperatures at fixed hours during the day to once-per-day readings of the 24-hour maximum and minimum. “Fixed” land stations are sometimes relocated, and even minor temperature equipment moves can change the microclimate exposure of the instruments. In other cases, the land use or land cover in the vicinity of an observing site can change over time, which can impact the local environment that instruments are sampling even when measurement practice is stable.

All of these modifications can cause systematic shifts in temperature readings that are unrelated to any real variation in local weather and climate. These shifts (or “inhomogeneities”) can be large relative to true climate variability, and can cause large systematic errors when calculating climate trends and variability for a single station as well as for the average of multiple stations.

For this reason, detecting and accounting for artifacts associated with changes in observing practice is an important and necessary part of building climate datasets. In GHCNm v4, shifts in monthly temperature series are detected through automated pairwise comparisons of the station series using the algorithm described in Menne and Williams (2009). This procedure, known as the Pairwise Homogenization Algorithm (PHA), systematically evaluates each time series of monthly average surface air temperature to identify cases with abrupt shifts in one station’s temperature series (the “target” series) relative to many other correlated series from other stations in the region (the “reference” series). The algorithm seeks to resolve the timing of shifts for all station series before computing an adjustment factor to compensate for any one particular shift. These adjustment factors are based on the average change in the magnitude of monthly temperature differences between the target station series with the apparent shift and the reference series with no apparent concurrent shifts.

There are three versions of GHCNm. They are:

- QCU: Quality Control, Unadjusted

- QCF: Quality Control, Adjusted, using the Pairwise Homogeneity Algorithm (PHA, Menne and Williams, 2009).

- QFE: Quality Control, Adjusted, Estimated using the Pairwise Homogeneity Algorithm. Only the years 1961-2010 are provided. This is to help maximize station coverage when calculating normals. For more information, see Williams et al, 2012.

ClimateExplorer would use QCU and QCF. ClimateExplorer does not need QFE because we would calculate our own normals, from the selected stations in the process discussed below.

Criterion 2 - quality over quantity

The three NOAA products have different sets of stations; GHCNm has about 28,000, GHCNd has about 120,000 and ISD has about 30,000 stations. All of these datasets would break ClimateExplorer if we didn’t add in extra controls over the display of data. Trying to display 30,000 stations on the map would break it. On lists of stations, we would have to prompt the user to filter the data or partially load the data in at a few hundred records at a time. However, the main problem isn’t technological. 30,000 stations is too many for humans to make sense of. We wanted users to look at their country and see no more than hundreds of stations for their region. We wanted them to think “ClimateExplorer doesn’t have my hometown but at least they have a nearby city. That’s acceptable.”

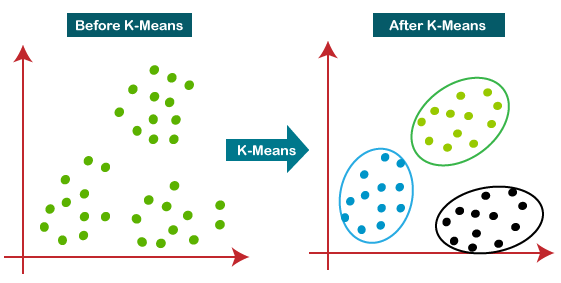

For the reasons stated above, no matter which dataset we decided upon, we would want to reduce the set of stations from tens of thousands to thousands. Therefore, we needed to try to group stations geographically and then select a station from the geographical group that had the best data. A quick search online about spatial grouping, came up with k-means clustering, so we started there.

K-Means Clustering algorithm

Wikipedia explains k-means clustering as:

a method of vector quantization, originally from signal processing, that aims to partition n observations into k clusters in which each observation belongs to the cluster with the nearest mean (cluster centers or cluster centroid), serving as a prototype of the cluster.

The above description seemed close to what we wanted. The n would be the number of stations in the cluster, and k could be how many clusters we’d end up with (wanting about 2,000) from which we could then select our best stations from within each cluster.

A question we had was: could k-means deal with geodetic coordinates (i.e., longitude and latitude). A stack-overflow question queried the issue; i.e., since k-means only uses Euclidean distance, would it work for places on the Earth - where we use the haversine formula to resolve the distances between locations with coordinates in latitude and longitude? The answer on stack-overlow was: “no, k-means will not work, use density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) with the Haversine formula to calculate distance.”

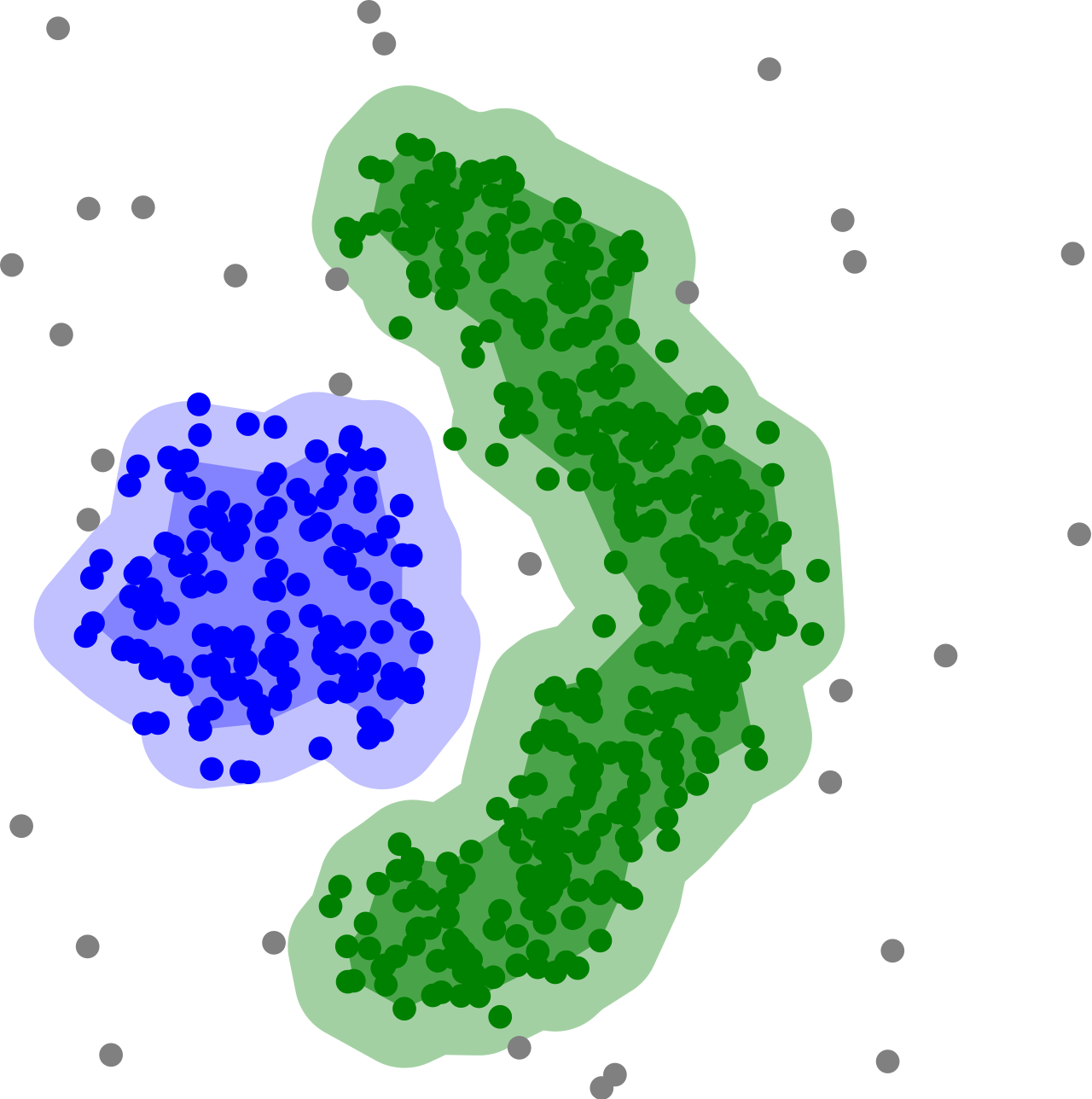

DBSCAN

Wikipedia explains density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) as:

a density-based clustering non-parametric algorithm: given a set of points in some space, it groups together points that are closely packed (points with many nearby neighbors), and marks as outliers points that lie alone in low-density regions (those whose nearest neighbors are too far away). DBSCAN is one of the most common, and most commonly cited, clustering algorithms.

That description also seemed like what we wanted (in the same way that k-means appeared appropriate). We also watched some videos about DBSCAN, such as: Clustering with DBSCAN, Clearly Explained!!! and read more on it; such as Clustering to Reduce Spatial Data Set Size.

It did not take too much longer to find a software package for DBSCAN implemented in .NET. The library did not provide a haversine formula for distances, but did provide an interface (ISpatialIndex

If you read the section on parameter estimation, DBSCAN requires three parameters. They are:

- Minimum number of points in a cluster (minPts). We wanted this to be low, only 3-5 as our use of the clustering was to prune out the lower quality stations in a region and end up with only one station in the cluster. We did not want clusters as the final product.

- An epsilon (ε) value. In our case this would be the maximum distance, in kilometres, between stations to still qualify as being in the same cluster. Initially, we didn’t really know what this value would be but thought that 100km seemed about right.

- The distance function. We had this figured out already because we knew we wanted to use the haversine formula.

After running the algorithm about 20 times, a minPts of 2 and ε of 75km (then selecting the best station from each cluster) resulted in a good distribution of stations around the globe. The problem with minPts of 2 is that some papers (and Wikipedia) suggest that this is not a valid value for minPts.

The low value of minPts = 1 does not make sense, as then every point is a core point by definition. With minPts ≤ 2, the result will be the same as of hierarchical clustering with the single link metric, with the dendrogram cut at height ε. Therefore, minPts must be chosen at least 3.

Therefore, the hierarchical clustering algorithm is more appropriate for this application. However, as the outcome would be no different and we’d already done all the work to get DBSCAN working, we decided to stay with the DBSCAN implementation.

Final station selection algorithm

There were also other considerations beyond the clustering algorithm. We wanted as much representation for each country as possible. Even if a station is close to a station in another country, we wanted to include both of those stations (presuming they were otherwise good stations). We also didn’t want to keep stations that only have old data - we wanted our stations to be current. The whole selection algorithm is as follows.

- Get all the stations listed in GHCNm

- Remove from this list any station that does not have any records in the last 10 years or where we can’t calculate the temperature anomaly (60 years of total data)

- If any country now has less than 5 stations, add the best stations for that country back into the list. (Better to have at least some representation for each country, even if it’s poor quality).

- Run DBSCAN at the country level, using an epsilon (i.e., ε or maximum distance between stations) of 75km and minPts of 2.

- Germany is very dense with lots of good stations, reduce ε to 45km for Germany

- The USA is fairly dense with good stations, reduce ε to 70km for the USA

- Remove any duplicate stations that exist from other datasets (e.g., if the station exists in GHCNm and ACORN-SAT, remove that station from the GHCNm collection - we will preference ACORN-SAT)

Once we had done all that we had our stations from GHCNm that could then be integrated into the list of all stations and then into ClimateExplorer.

Criterion 3 - data resolution

A downside of GHCNm is that it is monthly temperature records, not daily. We would prefer a daily record but have not found one that also fits with the other criteria. Another downside is that GHCNm is monthly mean, not maximum and minimums temperatures. Temperature gauge recording traditionally records the minimum and maximum. GHCNm has averaged the minimum and maximum and then averaged to a monthly value. This means some of the interesting graphs (e.g., number of days of frost) aren’t available.

As the data is monthly mean, we only need 12 values for the year, rather than the 730 values we have for stations with daily minimums and maximums. Therefore, storage space limitations disappear if we use GHCNm. When we include the adjusted (GHCNm call this QCF) and unadjusted (QCU) records, that’s still only 24 values a year.

Criterion 4 - records, not modelling

From the GHCNm website:

The Global Historical Climatology Network monthly (GHCNm) dataset provides monthly climate summaries from thousands of weather stations around the world. (emphasis mine)

By using GHCNm, we have only included data from really existing stations.

Criterion 5 - precipitation

Precipitation data was available for each of the NOAA products. Given that we had all but settled on GHCNm, we needed to look at the GHCNm precipitation data. GHCNm Precipitation is currently a beta product.

The Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) Monthly Precipitation, Version 4 is a collection of worldwide monthly precipitation values offering significant enhancement over the previous version 2. It contains more values both historically and for the most recent months. Its methods for merging records and quality control have been modernized.

The data set is updated typically in the first week of each month and available through the links below.

The precipitation data uses the same identifiers as GHCNm, thankfully. Surprisingly, and annoyingly, the access method and the format of the data between temperatures and precipitation are different. GHCNm temperature records are all in one big file, 1.5 million rows - about 160MB. We wrote a preprocessor to iterate through the file, pulling out each station and year of records - if a year didn’t have 12 months of recordings, the year was discarded. We had assumed GHCNm Precipitation would follow the same data structure. Unfortunately, each station is stored as a single file on their server, available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/ghcnm/v4beta/. We needed to write a HTTP client that would connect to the server and download each file for the selected stations.

Future extension

By using GHCNm, we are not able to display some of the interesting charts that rely on daily minimum and maximum temperatures and daily precipitation. A future extension could be to integrate GHCNd with GHCNm within ClimateExplorer. It is likely that the integration would be seamless as ClimateExplorer already has significant abstraction setup to support different datasets for Australia and New Zealand (e.g., ACORN-SAT vs standard BoM data). These daily data would only have unadjusted records (GHCNd only has raw values), but that would not be a problem as we could drop back to GHCNm when comparing adjusted vs raw values.

Another bonus is that the identifiers are the same for stations between GHCNd and GHCNm, though it would have been possible to identify stations by latitude and longitude anyway.

The only real concern in integrating GHCNd is whether we could support the increased storage space required. It would be a jump from 24 records per station, per year (12 for mean temperature and 12 for precipitation) to 1095 records per station, per year (365 for min temperature, 365 for max temperature and 365 for precipitation).