What’s up with temperature anomalies?

An anomaly is anything that is not normal. In science and mathematics, series of related numbers can be compared to discover anomalies within the series. To calculate a climate anomaly, we need to first decide what is “normal”. Climate scientists have decided that any 30-year average of weather (i.e., average temperatures, rainfall or other phenomena) to be a sufficiently long enough period of time to use as a basis for a climatological normal (see previous blog entry for more). Below we’ll discuss why and how climate anomalies are used in conjunction with a climate normal.

Temperature anomaly

In climate science, a temperature anomaly has a specific meaning and method for calculation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) explain it as:

[…] the difference from an average, or baseline, temperature. The baseline temperature is typically computed by averaging 30 or more years of temperature data. Anomalies vs. Temperature

Anomalies can be used to determine how much a location has increased or decreased in temperature compared with the climate normal for that location.

For example, the average maximum temperature for Hobart (Tasmania, Australia), 1961-1990, is 17.2°C. If a yearly average max temperature is 18.5°C, the anomaly is 1.3°C. If a yearly average max temperature is 15.7°C, the anomaly is -1.5°C.

Comparing between locations

Another question we may want an answer to is: how do we compare temperatures from different locations to see if there is a general trend?

It would be great to not use anomalies. Why not simply average the raw temperature values (the absolute temperatures)? That would give results that are a lot easier to understand and relate to. If we wanted to compare Hobart with Darwin (Northern Territory, Australia) - two cities at the extremes of Australia - we can do that using absolute values.

Below is a table with Hobart’s and Darwin’s yearly average maximum temperature from 2011 until 2020. It also has the combined yearly average (third column) and the total averages (last row).

Table 1 (in °C)

| Year | Hobart | Darwin | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 17.52 | 31.63 | 24.58 |

| 2012 | 18.10 | 32.33 | 25.22 |

| 2013 | 18.11 | 32.68 | 25.40 |

| 2014 | 18.26 | 32.64 | 25.45 |

| 2015 | 17.63 | 32.61 | 25.12 |

| 2016 | 18.22 | 33.24 | 25.73 |

| 2017 | 18.45 | 32.78 | 25.62 |

| 2018 | 18.19 | 32.82 | 25.51 |

| 2019 | 18.65 | 32.98 | 25.82 |

| 2020 | 17.70 | 33.10 | 25.40 |

| Total | 18.08 | 32.68 | 25.39 |

On their web page about anomalies, NOAA’s explanation for their use in climate science does not lead with the best reason for using them. They discuss their use in regards to location.

When calculating an average of absolute temperatures, things like station location or elevation will have an effect on the data (ex. higher elevations tend to be cooler than lower elevations and urban areas tend to be warmer than rural areas). However, when looking at anomalies, those factors are less critical. Anomalies vs. Temperature

However, if temperature records were as good as the recent records for Hobart and Darwin, there would be no need to use anomalies. We have shown above that finding the average between wildly different locations is no big deal (it’s about 25°C for Darwin and Hobart).

NOAA’s second paragraph states the best reason to use anomalies; because climate data is irregular. The data is irregular because

- Stations start recording data at different times (some stations started recording more than one hundred years ago while others only started recording this year)

- There are often breaks in records, sometimes running for multiple consecutive years, sometimes with sporadic missing records

- Stations stop recording permanently even though they have long runs of reliable readings

With all of these conditions applying, it’s possible that Table 1 could look like Table 2, below. In Table 2, a fictitious example, Darwin’s station started recording in 2013 and shutdown at the end of 2019, while Hobart’s records are unavailable for the years 2015 and 2018.

Table 2 (a fictitious variation of Table 1, in °C)

| Year | Hobart | Darwin | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 17.52 | 17.52 | |

| 2012 | 18.10 | 18.10 | |

| 2013 | 18.11 | 32.68 | 25.40 |

| 2014 | 18.26 | 32.64 | 25.45 |

| 2015 | 32.61 | 32.61 | |

| 2016 | 18.22 | 33.24 | 25.73 |

| 2017 | 18.45 | 32.78 | 25.62 |

| 2018 | 32.82 | 32.82 | |

| 2019 | 18.65 | 32.98 | 25.82 |

| 2020 | 17.70 | 17.70 | |

| Total | 18.13 | 32.82 | 24.68 |

Note: we have applied a rule here that if a year is missing an average temperature we nevertheless average what is available. We could have a rule that if any year is missing, we refuse to average, and ignore the whole year. That would invalidate half of the results in this case, even though only one quarter of the initial data is missing. If we wanted to analyse many locations, we would even more frequently have to throw out whole years, or come up with another method for how many missing years are acceptable to still form a valid average. Once we group tens or hundreds of stations together, it’s very likely that some may experience issues in maintaining records on any given year.

Why anomalies are required

It’s clear that the yearly averages for 2011, 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2020 in Table 2 are wildly inaccurate. There were no real fluctuations in temperature, but the averages suggest there are. It’s all due to missing data.

Instead of using absolute temperature averages, climate scientists are forced to use anomaly averages because the historical record of temperatures are not standardised, long running, or reliable enough to use absolute temperatures.

Below is a table where the same missing years of data exist as Table 2, but average anomalies are used instead of absolute temperatures.

Table 3 (a fictitious variation of Table 1, in anomalous °C)

| Year | Hobart | Darwin | Average anomaly |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | -0.61 | -0.61 | |

| 2012 | -0.03 | -0.03 | |

| 2013 | -0.02 | -0.14 | -0.08 |

| 2014 | 0.13 | -0.18 | -0.03 |

| 2015 | -0.21 | -0.21 | |

| 2016 | 0.09 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| 2017 | 0.32 | -0.04 | 0.14 |

| 2018 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2019 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| 2020 | -0.43 | -0.43 | |

| Total | 18.13 | 32.82 | -0.07 |

With 25% of the records missing it would be difficult to have much confidence in the results no matter what analysis we attempt and yet Table 2 and Table 3 are completely different.

If you compare Table 3’s 2011 anomaly (-0.61°C) with Table 1’s anomaly (24.58°C - 25.39°C = -0.81°C), the difference is only 0.20°C. However, Table 2’s 2018 absolute temperature average (32.82°C) compared with the Table 1’s temperature average (25.51°C), shows a difference of 7.31°C!

It is clear that an analysis using anomalies is a much more reliable method when the temperature record contains missing data.

Once we’re happy that this technique works well with some missing data (hopefully much less than 25%!), we can use it to aggregate not just Darwin and Hobart, but whole regions and ultimately, the world. ClimateExplorer has recently applied these calculations for all of Australia.

Reference period

The reference period is the last aspect of climate anomalies to discuss. The reference period is the time period that is selected to calculate the base average (the “climate normal”). The most important part of this process is to select a reference period that is representational for all of the locations in the collection. For instance, there is no point choosing 1901-1930 if most of the stations in the group weren’t operating during that period.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) have selected 1961-1990 for their reference period (see ACORN-SAT). The UK Met Office Hadley Centre generally use the same reference period (see HadCRUT5). NASA GISS use 1951-1980.

The reference period selected will not change the shape of the resulting data and graphs, only the magnitudes of the anomalies. If the years 1991-2020 were selected, anomalies will rarely be above zero because that period is (currently) one of the hottest periods on record (i.e., most years on the temperature record will be colder than the period 1991-2020).

When compiling data for the Australian anomalies for ClimateExplorer, we used the same reference period as the BoM (1961-1990) while also requiring that each station have records for at least half of those years. When doing so we found that Burketown, Eucla, Learmonth, Morawa, Robe, Snowtown, and Victoria River Downs did not have enough records during that period. Those stations have been excluded from our analysis.

Another approach

There are other ways we could cope with missing data and still use absolute temperatures. One of those methods is interpolation. The drawback of interpolation is that it’s more complicated to implement and - more importantly - more difficult for people to understand. If we want to be able to convey how we can determine that global warming is happening, the simplest valid explanation is what we should lead with.

Climate sceptics and anomalies

We have explained why climate scientists present their large aggregation results (e.g., the global average temperature) as temperature anomalies. There is sufficient information to show that sceptics’ complaints are unfounded. Nevertheless, what follows is a short discussion of some of their grievances.

Weather vs climate

[…] in the real-world, people don’t experience climate as yearly or monthly temperature anomalies, they experience weather on a day to day basis, where one day may be abnormally warm, and another might be abnormally cold. (WUWT, 2023)

The statement from Watts Up With That? (WUWT) isn’t false, it’s merely anti-scientific. Science is about trying to go beyond personal experience and common sense; it’s about analysis to justify hypothesis. Climate science has nothing to do with anyone’s experience of weather, it’s an analysis of long-term trends; for instance, trying to see if there is evidence of global warming from observed heating caused by greenhouse gases under controlled conditions (see Eunice Foote, 1856). In this situation, a human’s sense of temperature is totally inadequate.

Climate conspiracy

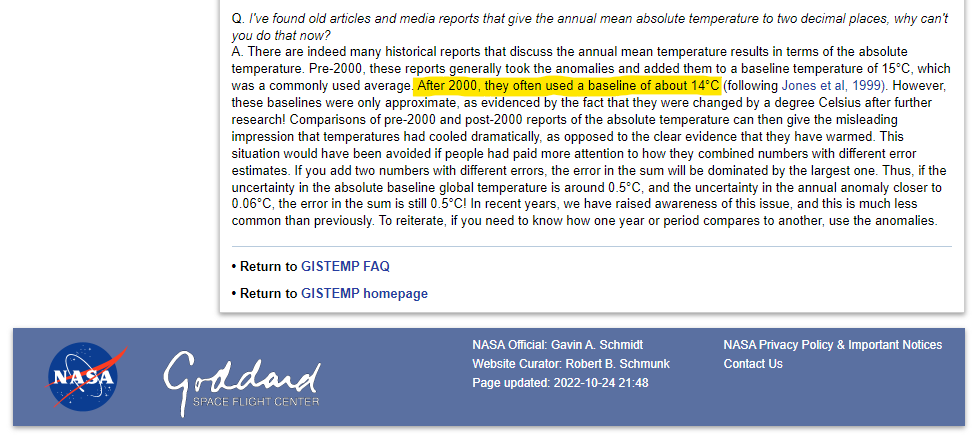

Not only is there nothing interesting in the two graphs in the WUWT article (“real” vs “anomaly”) - it’s the same graph with different scales on the y-axis - the article claims that NASA Goddard Institute of Space Studies has removed a method for converting from anomalies to absolute values.

Of course GISS removed it from that page as seen today, because they don’t want people doing exactly what I’m doing now […] (WUWT, 2023)

However, not only has the information not been removed, it has been expanded to explain why the approach is fraught with errors, and why anomalies should be used rather than absolute temperatures when analysing global averages. (GISS FAQ was last updated Mar. 18, 2022. The Watts Up With That? article was written Mar. 12, 2023 - there is no excuse for missing this information).

From: The Elusive Absolute Surface Air Temperature, 2022

From: The Elusive Absolute Surface Air Temperature, 2022

Urban Heat Island

WUWT also state that climate scientists don’t adjust for biases of Urban Heat Island (UHI). The BoM explain that eight locations in their 112 ACORN-SAT sites are affected by this phenomenon.

[…] four ACORN-SAT locations (Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Hobart) were defined as urban in the initial classification, and four more (Laverton, Victoria; Richmond, New South Wales; Townsville and Rockhampton, Queensland) as urban-influenced […] These eight locations remain a part of the ACORN-SAT dataset, as they are important for monitoring changes in the climates in which many Australians live. However, they are not included in assessments of the warming trend across Australia or the calculation of national and State averages. (ACORN-SAT FAQs - emphasis mine)